Focus

Operations

How will you run your business? See the tactical decisions brands make in order to deliver on their mission and promise.

Define your purpose

Four years after Airbnb began, co-founder Brian Chesky contacted Douglas John Atkin and asked him to help define Airbnb's brand. Douglas responded, "I think that instead of the brand, we should figure out the purpose of Airbnb and its community. There clearly is a huge and vital community of Hosts, Guests, and Employees. Let's figure out what role Airbnb plays in their lives and why they are committed to it. If we can do that, then it will be much easier to figure out what Airbnb's brand is."

Douglas developed Airbnb's purpose 'Belong Anywhere' based on these three ingredients:

- Ground it in truth. Douglas' first step was understanding the Airbnb experience from the users, not the executives. For three and a half weeks, Douglas spoke to 485 hosts, guests, and employees face-to-face worldwide. Their conversations focused on what drove loyalty to the brand, from the transactional to the emotional.

- Make it enormously ambitious. The purpose had to be "huge enough to seem almost impossible to achieve...so that for a hundred years or more, people will keep trying." That meant it also had to be "exciting enough to get out of bed for and inspirational enough to keep you going through the tough times."

- Make it specific but also just broad enough. The purpose had to act as a guardrail to keep the company focused but also be broad enough to inspire and encompass future innovations and products. Airbnb's Experiences, which focuses on things people do during their stays, and Open Homes, their philanthropic venture, were launched using their purpose as their guide.

Design beyond a 5-star experience

Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky believes a five-star rating is the standard for most marketplace businesses. Unless the experience is horrible, people generally give five-star reviews. However, as Brian describes, "If you want to build something that's truly viral, you have to create a total mindf*ck experience that you tell everyone about."

To create those ultimate experiences, Airbnb worked with Pixar animators to storyboard every frame of a user's experience—from first logging on to the site to the moment a Guest returns home. Each storyboard included a one-star experience all the way to a seven-, ten-, or even eleven-star experience.

The point of the exercise is that while an eleven-star experience may not be feasible, the seven-star experience you thought was unattainable before now seems doable. "That's the sweet spot," Brian concludes, "You have to almost design the extreme to come backward."

Do things that don't scale

In the first years of Airbnb, when their number of users was low and primarily located in New York, an investor gave co-founder Brian Chesky this advice: “Go to your users. Get to know them.” Brian’s response was, “But that won’t scale. If we’re huge and we have millions of customers, we can’t meet every customer.” The investor replied, “That’s exactly why you should do it now because this is the only time you’ll ever be small enough that you can meet all your customers, get to know them, and make something directly for them.”

With that advice, founders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia flew to New York. They went to every host’s house, asking to meet and interview them and sometimes even staying with them. They also went door-to-door signing people up, hosted meet-ups, and approached people wherever they could to tell them how to monetize their apartments. During these conversations, the founders also observed how hosts used the Airbnb website. Each week, they would incorporate any feedback they received which led to breakthrough insights, like:

- How to educate users on uploading and taking professional photos for their properties

- Which profile details would make hosts more comfortable in allowing guests to stay with them

- What makes a great user experience when it comes to customer support

Make principled decisions in a crisis

In just eight weeks, Airbnb lost 80% of their business due to the pandemic. Co-founder Brian Chesky learned quickly that "there's not a lot of data in a crisis." Instead of relying on data-driven decisions, he needed to act swiftly and make principled ones. As he explains, "A principled decision is if I can't predict the outcome, how do I want to be remembered?"

Chesky developed four fundamental principles to help guide the company during this time:

- Principle 1: Act fast. Be intuitive. Be courageous. Going into the pandemic, Chesky had concerns that Airbnb was becoming too bureaucratic. There were at least ten divisions, each having their own operations, design, and marketing teams. The pandemic forced Chesky to pull the trigger on rebuilding the company from the ground up, consolidating all divisions so that there would only be one operations group, one design group, and so on for the entire company.

- Principle 2: Preserve cash. Airbnb cut the size of its staff by 20%, reduced executives' pay, and reduced the Marketing budget to zero. Chesky instead gave over 100 press interviews that year.

- Principle 3: Act with all stakeholders in mind. Brian approached the pandemic with the idea that Airbnb needed to be as "generous as we possibly could be." Each person who lost their job was given 14 weeks of severance and one year of health insurance. The Airbnb recruitment team also helped them find new jobs. Guests received full refunds for any cancellations due to the pandemic. Airbnb also dispersed $250 million amongst Hosts to compensate for the $1 billion in cancellations that occurred.

- Principle 4: Play to win the next travel season and continue to move forward. Within three weeks, Airbnb enacted a plan to cut back on products like luxury home rentals and hotel expansions and shifted towards rural vacations that people can book within a day's drive, long-term rentals, and virtual events.

Ask users about the product of their dreams

At the beginning of Airbnb, co-founders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia would sit down personally with customers to understand how they could improve their business. However, they didn't ask about the product that they had already built. They found that by asking questions like, 'What can I do to make this product better?' they received small, uninspiring answers.

To gain the most insightful feedback, they asked about the product of their customers' dreams, with questions like:

- What can we do to surprise you?

- What can we do, not to make this better, but to make you tell everyone about it?

Create a singular roadmap for the entire company

Instead of multiple roadmaps spread over multiple divisions, CEO Brian Chesky consolidated Airbnb down to one division made of functional teams that share a singular roadmap. This rolling two-year roadmap contains every Airbnb project being worked on and is aligned to a May or November release date.

For each project, Brian reviews all of its pieces, including the marketing. He explains, "Every week, I would try to see the equivalent of at least a semi-assembly of the entire new product we were working on, which allowed me to identify the different bottlenecks happening in the company."

While the road map was designed not to change for the upcoming month, it is reviewed and updated monthly, allowing the next two years to stay fluid. As for unexpected events, Airbnb ensures that enough resources are in reserve to pivot as needed.

Combine product management with marketing

Instead of having product managers, those who lead the development of the product, and outbound marketers, those who promote the product, Airbnb consolidated those responsibilities into one Product Marketing role. As co-founder Brian Chesky explains, "We...connect product and marketing together. Product managers at a company are usually like chefs, marketing are like waiters, and chefs never allow the waiters in the kitchen, or they get yelled at. And I thought, well, what if you actually have them collaborate on a product?"

This shift allows outbound marketers, who have in-depth knowledge of customers and how to tell a story, to collaborate in the innovation process from the beginning. It then becomes the responsibility of product marketing to promote the product but also to "make sure we understand the story we're telling, who the product's for, and make sure everything we deliver ships to that product."

Kick off every project with a press release

At the beginning of every new initiative, Amazon product managers write an internal press release announcing the product as if it were finished. This page-and-a-half announcement centers around how the product solves a specific customer problem and how it will "blow away existing solutions."

The goal is to keep the writing simple. Paragraphs should have no more than three to four sentences and not include any "geek-speak." As a guideline, Ian McAllister, Director of Amazon Day, recommends writing it as if you were Oprah explaining it to her audience. If the press release doesn't "sound interesting or exciting," the product manager continues to revise it or cancels the project's development.

While creating the press release takes a lot of time, Amazon finds it quicker and less expensive than iterating on the product itself. The press release also serves as a guide in the product's development to help avoid scope creep.

Start with design

Unlike most companies who engineer their products first then hand it down to designers, Apple reverses this order and begins with design. In fact, everyone else in the organization has to conform to the designer's vision, no questions asked. When creating the Apple II, Jobs had the engineers remove the cooling fan because he believed that a quieter computer is a more beautiful computer. It didn't matter to him that the technology wasn't invented yet—it was up to the engineers to figure that out, which they did.

Spend your advertising budget only on your most popular product

When Jobs returned to Apple, he consolidated the advertising budget into one single budget where only the most popular products would receive ad dollars. By limiting the number of products promoted, heavily promoted products indirectly drove sales for Apple's other products. So when customers came into stores looking for the iPod, they were also exposed to iMacs as well.

Avoid focus groups, consultants, and market research

Imagine if the first iPhone had a stylus and a retractable keyboard? That's what Apple believes would have happened if they relied on focus groups to inform the design. To Apple, customers don't innovate, they only iterate what they have seen before. So people actually don't know what they want until you show it to them.

But this doesn't mean to stop listening to customers. Instead know your customers so well that you know what they want before they realize it themselves.

Increase anticipation with vigilant secrecy

The cost of information being released early about an upcoming innovative product is too risky for Apple. It dampens the anticipation, gives competition time to respond, allows openings for critics to criticize the idea rather than the actual product, and finally steals the thunder from the existing product line.

So it's not surprising that the penalty for revealing any Apple secret, intentionally or unintentionally, is immediate termination and lawsuits. But Apple doesn't stop there.

- Employees must sign agreements stating that they will not even tell their spouses or kids about the projects they are working on.

- Visiting guests are not to be left unattended even in the cafeteria and are asked to not share or post any details about their current location.

- Teams are purposely kept apart and don't know what the other one is working on. On launch day, they have no idea what other features in the same product will be announced simultaneously.

- New employees don't know what their exact roles are until after onboarding.

- Organization charts don't exist. They are considered information that employees don't need and outsiders shouldn't have.

- Plainclothes Apple security agents are believed to hang out at nearby bars to see if employees are staying quiet.

Expand your business by finding owners, not investors

Chick-fil-A reinvented the fast food franchise model by focusing on finding fully committed owners, which they call Operators, who will be present every day to maintain high quality standards. But to do find the best people, Chick-fil-A first removed the need for any large upfront costs on the Operator's part. This allowed Chick-fil-A to select new owners based on character and values, rather than the size of their wallets.

The Operator's Agreement for Chick-fil-A works like this:

- The Operator makes an initial low and fully refundable investment of $10,000.

- Chick-fil-A supplies the Operator with everything that is needed. They select the location, build the restaurant, and purchase the equipment.

- The Operator is committed to a single store and is not allowed to have other businesses on the side.

- The Operator pays Chick-fil-A 15% of gross sales, plus 50% of net profits.

- Everything else is left up to the Operator. He or she is now the CEO, manager, president, and treasurer of the business and is in charge of all operations.

Out of 20,000 applications submitted each year, Chick-fil-A selects only .4%. Their high standards come from a desire to make each relationship last for life, and with less than a 5% turnover rate, in an industry where 30-40% is common, they are succeeding.

Find your Blue Ocean Marketing Strategy

Chick-fil-A's marketing goal was to find an uncontested market space, and then dominate it. With a limited budget, they couldn't compete with TV ads—but what they could do, was focus on billboards, 3D billboards to be precise. At the time, billboards were used only to showcase price points and tell people which exit to take. Chick-fil-A, however, found their Blue Ocean by using billboards to build an emotional connection with their brand. Their rules for billboards were simple:

- Create advertising that is unexpectedly fun. Every billboard had to be endearing and make them laugh.

- Don't show the product. You can't build an emotional connection around a picture of a piece of chicken on a bun, so don't try.

- Don't show prices, deals, or tell people where to turn. Focus on connecting with people through humor, not selling them something. See first rule.

Decentralize innovation

Instead of relegating innovation to a few experts, Chick-fil-A opens up their innovation process to the entire organization.

Staff from each department volunteer and then are trained to become innovation coaches. They then go back to their teams as consultants to help facilitate innovation using Chick-fil-A's innovation methodology:

- Understand the problem and the audience that is experiencing it.

- Imagine ways to creatively solve the problem. Specific creative thinking techniques are used in collaboration spaces found in the Hatch, Chick-fil-A's onsite 32,000 square foot innovation center.

- Prototype your vision using materials from anything that can be found in the Hatch from wood to foam board. One innovation team built a fully functioning replica of a restaurant to try different layouts.

- Validate your creation with a dress-rehearsal of sorts that brings all departments and stakeholders together to stress test the prototype.

- Launch your creation into the marketplace.

From the start of the process, each team member is encouraged to play the part of a particular thinking type:

- The Investigator is in charge of asking why to get to the root of the problem.

- The Inventor asks why not and proposes solutions.

- The Investor narrows the ideas down to the best one or two.

- The Implementer finds way to get things done even if it means breaking some rules and asking for forgiveness later.

Create a brand architecture with your brand essence at the center

Over ten years ago, Chick-fil-A wanted to relay to its staff, in the simplest visual format, how each brand touchpoint, although separate, connects everyone together across the organization. They started by placing all touchpoints around a wheel design to breakdown the stigma of organizational silos. Everyone is responsible to work around the wheel and have influence in all projects, even if they are not directly accountable. At the center of the wheel, aligning everyone together, is their brand essence.

A brand essence is a short rallying cry created to embody a brand cause, mission, promise, and personality. Chick-fil-A defines theirs as: Where good meets gracious.

- Where: Anywhere, not just in a restaurant, but any encounter with the brand

- Good: Good people, good food, good environment, good service

- Meets: Any encounter shows genuine care for another person

- Gracious: Hospitality with a personal touch that people don't expect

Test, survey, then launch

All new products and services are first tested by Chick-fil-A in roughly 60 to 100 stores for a one-year period. During this time, Chick-fil-A surveys customers to see if the new product or service are consistent "with what they perceived to be the Chick-fil-A brand."

When choosing between shoestring and waffle fries, Chick-fil-A used this methodology and found that, even though waffle fries were more expensive, customers saw them as a better brand fit. Shoestring fries were trying too hard to be like everyone else, and waffle fries were visually different, and perceived to be more nutritious.

Don't undermine the value of your brand with coupons and discounts

To Chick-fil-A coupons and discounts scream, “Our products are not worth full price." Instead of being a "transaction-chasing" brand like other fast-food restaurants, Chick-fil-A chooses to build their brand through personal relationships.

Prioritize innovation by using the 70-20-10 rule

Google uses the 70-20-10 rule to ensure that their time and resources are spent on improving their core products but also on growth and brand new innovations.

How Google allocates their resources:

- Spend ~70% on incremental improvements to your core product that can be done in a year. This ensures that the core business always gets the majority of the resources. Think 'ship and iterate.'

- Spend ~20% on expanding products into new markets. These projects can take up to 3 years to implement but ensures that you allocate resources for growth and expansion.

- Spend ~10% on completely new ideas that have a high risk of failure but can be groundbreaking. This allows moonshot ideas to have a chance without fear of getting their budgets cut.

Google's top 100 projects are managed on a spreadsheet and then organized into these three buckets. The prioritization of the list is reviewed and adjusted semi-quarterly and is always available for staff to see on the company's intranet.

Test and measure everything

Anything Google does more than once is measured and then improved upon. For Google Search alone, they will conduct over 8,000 A/B tests and more than 2,500 one-percent tests in a given year. That averages out to roughly 30 experiments a day so that they can better understand what works best for their users.

All testing is done in-house as Google finds using consultants to be too costly. They also don't want to run the risk of missing out on any insights that might have been overlooked by non-Googlers.

Measure user experience with HEART

Without being able to effectively measure the success of your products or services, it will be impossible to know if your choices were right, wrong, or somewhere in the middle. To solve for this, Google measures the quality of the user experience using the HEART method:

- Happiness: How satisfied are users with your product?

- Engagement: How how long do users engage with your product?

- Adoption: How many users subscribe, enroll, or sign up for your product?

- Retention: How many users consistently come back to your product?

- Task success: Can users accomplish their goals quickly and easily?

How to use the HEART method:

- Step 1: Set goals. When setting goals, Googlers will ask themselves: "What do we want a customer to say after using our product?”

- Step 2: Define signals. Map your goals to related user actions, behaviors, or attitudes.

- Step 3: Choose metrics. Based on your signals, create measurable and trackable metrics.

See an example of the HEART method in action.

Set goals with Objectives and Key Results

At the beginning of each quarter, Google leadership sets clear company-wide goals called OKRs, Objectives and Key Results. Based on these corporate OKRs, staff create personal OKRs that align with the organization's. Everyone's OKRs are then posted publicly on the intranet, right next to the person's phone number and office location.

How OKRs work

- Objectives are qualitative descriptions of what you want to achieve. They should be short, motivational, and challenging. To avoid overextension of your teams, only pick three to five Objectives.

- Key Results are quantifiable ways to track your progress towards an Objective. They must be tangible, measurable, and unambiguous. Choose around three Key Results for each Objective.

Each Key Result is graded on a scale of 0.0 to 1.0 and then averaged together to determine the final score for the Objective. The "sweet spot" score is around 60-70%. Google has found that allowing this much room for failure, empowers employees to set stretch goals that help keep the company innovative and advancing forward.

Run your ideas through an innovation cycle

At Netflix, if an employee has an idea that they're passionate about, there is an innovation cycle process to bring it to life.

Step One: Farm for dissent or socialize the idea

Create a shared memo explaining your idea and invite colleagues to rate it on a scale from -10 to +10 with their explanation and comments; or set up multiple meetings to stress-test the idea.

Step Two: For a big idea, test it out

Nothing works better than a small, isolated test for proposals that involve a lot of time, work hours, and resources. Tests take place even when those in charge are dead set against the idea.

Step Three: As the informed captain, place your bet

This is not a democracy, consensus, or a vote. As the person in charge of the project, you take full responsibility. You do not need anyone's permission, agreement, or sign-off to move forward with an idea, no matter its cost or size.

Step Four: If it wins, celebrate it; if it fails, sunshine it

Successes are celebrated by all and especially by managers who expressed dissent early on publicly saying 'You were right, I was wrong.' Failures are not grounds for termination but learning opportunities on how to succeed better next time. Informed captains are required to write an open memo to the entire company explaining what happened and the lessons that were learned.

Stop doing test pilots

Unlike its competitors, Netflix doesn't believe in testing TV shows with just one episode before committing to a full season. Instead, they buy or commission a series from start to finish. Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos describes the strategy like this: "In our research of more than 20 shows across 16 markets, we found that no one was ever hooked on the pilot. This gives us confidence that giving our members all episodes at once is more aligned with how fans are made." This approach also places more accountability on the show's project owner, who can't hide behind the excuse of 'it tested really well.'

Plan quarterly, not yearly

The future can't be predicted and any time Netflix tried, they were always wrong—especially when it came to budgeting. Instead, the time wasted on yearly planning is now spent doing quarterly planning and a rolling three-quarter budget. To Netflix, it's a horrible idea to hold off on growth opportunities because of budget constraints set months ago.

Expand into completely new industries that align with your purpose

Although they are best known for their clothing line, Patagonia has never limited themselves to only one industry. Instead, they expand their business based on the positive impact it could make on the environment.

- First, they began as a blacksmithing company making reusable climbing tools that protected the environment.

- Next, they entered the clothing industry with a focus on creating durable clothing that would stay out of landfills.

- Then, they started a book and film division focused on educating people about environmental issues.

- Now, Patagonia's future lies in regenerative and restorative agriculture with Patagonia Provisions.

With each expansion, Patagonia is always asked "What do a bunch of climbers know about this?" or "What does a clothing company know about that?" And their answer is always "nothing," but if it helps save the planet, they will commit to it 100%.

Support social causes that align with your mission

There is no question to Patagonia's commitment to their mission. In their history, they:

- Sued the Trump administration to protect Bears Ears National Monument

- Continually donate 1% of their sales revenue to fight climate change, even in years when they don't make a profit

- Donated 100% of Trump's tax cuts to environmental groups

However, what makes them so purpose-focused is that they see everything in the world through the lens of environmental conservation. Their support of Planned Parenthood comes from the viewpoint that the non-profit is working towards "the single greatest cause of environmental problems: overpopulation."

Change the entire way your business runs if it doesn't align with your values

When Patagonia realized that the conventional cotton production process was creating severe environmental and health issues, they abandoned the process completely for an organic cotton supply chain. At the time though, Patagonia had no idea how to do this, but because it was the right thing to do, they created an organic supply chain on their own. Within eighteen months, they completely reengineered their operations and were able to:

- Remove all toxic dyes, which meant saying goodbye to the color orange for a while until they could find an environmentally safe replacement.

- Make sure that all cotton fibers were certified and could be traced back to the bale.

- Make their farmers use regenerative growing practices.

- Make their ginners and spinners clean their equipment before running any Patagonia products, no matter how small the quantity.

Grow strong, not fat

In the late 80s, Patagonia was growing fast—50% a year fast. They started opening more locations and increasing their inventory production. But after the 1991 recession, dealers started cancelling orders and inventory began to build. Patagonia now had too many people with too little work being overseen by too many layers of management. With an inflated product line, they also had neglected to take into account the cost of having to design, produce, warehouse, and catalog all these products.

After almost losing the business because of this, Founder Yvon Chouinard decided to change their growth mindset from growing fat to growing strong. Patagonia began looking at their business as if they were going to be around for the next 100 years having to take responsibility for the decisions they made today.

As a result, Patagonia stopped looking at quarterly earnings and setting yearly growth projections. "One year we will grow 3% another year we will grow 20%," Yvon explains—and he is okay with that. Patagonia now chooses to wait for the customer to tell them how much product to make. Slow or no growth just means that profits have to come from "being more efficient with operations and living within [brand's] means."

Patagonia also now knows exactly how many people they need to hire if they want to add just one product to their line.

Choose values over higher margins

When changing their operational structure from conventional to organic cotton farming, Patagonia wanted to understand what impact this higher operational cost would have on sales. Through customer surveys, Patagonia found that quality was the most significant reason that customers bought from them. Brand name and price were secondary, while environmental concerns were last.

Understanding this customer perspective gave Patagonia some room to raise prices slightly, but to keep prices from exceeding two to ten dollars over conventional cotton cost, they reduced their margins in partner retail spaces. Products that could not meet the margin goal were limited to Patagonia's own retail stores and mail-order channels to keep prices down.

Cannibalize your newest products to maintain the highest quality

When focusing on quality, there will come a day when you look at a current product and say 'I can do better.' For Patagonia, that day came only a few months after their new environmentally-friendly chocks came to market.

Having received feedback from fellow climbers that there may be a better way to make them, Patagonia had a choice: 1) Give their working new chocks their day in the sun knowing that quality could be improved or; 2) Start again...immediately.

True to their values, they scrapped all of their tooling, invested in all new designs, and came out with a new modernized chock. Coincidentally, that very same month a competitor came out with an exact copy of Patagonia's old and now very obsolete chock design.

Test, test, and test again

Patagonia tests every product out in the field until something fails. They then strengthen that part, test again until something else fails then strengthen that part. They repeat this process ad nauseam until the product is durable as a whole.

Top climbers, surfers, and endurance athletes are also provided gear and sometimes salaries and benefits "to wear [Patagonia] clothes, in order to give...feedback and help with design issues." Patagonia even does a "quick and dirty" test of competitor products to see if any of their ideas are worth pursuing.

Choose concurrent manufacturing over assembly-line manufacturing

Too often a company will hand their designs over to a production team without understanding the full development process upfront. This assembly-line style can lead to the production team changing design elements to meet production requirements and the sewing team altering construction to meet their own practices. Patagonia has found that by all teams working together upfront to set standards, the product's purpose, process, and intended performance are never jeopardized.

Always spot check for quality when you set up manufacturing for the first time

As Yvon Chouinard puts it: "If a button falls off in your customer's hand as she pulls the pants out of the washing machine..[she] will never again fully trust your claim to quality."

Patagonia has suffered through every stage of trying to find the best place to spot check for quality—at the factory level, at the sewing machine level, and also just before the sewing machine level. What they found was that if you take "extraordinary steps to set up the manufacturing correctly the first time, it is much cheaper than taking extraordinary steps down the line."

Ensure that the values of your vendors align with your own

As a brand that relies on outside vendors to make their apparel, it has never made sense for Patagonia to use the same vendors that sew shorts for Walmart one day and for Patagonia the next—the quality and attention to detail just cannot be trusted. Instead, Patagonia looks for partners that meet their "4-fold" set of standards: Business, quality, environmental, and social standards.

"We audit potential partners to determine how they manage workers, we interview workers to determine their perspective on the factory, and we engage Civil Society to verify that the factory has positive employment record," writes Yvon Chouinard. If they find a partner that meets their standards, but does not have a strong company culture, Patagonia will send people to train the vendor's HR team, so that both cultures align.

Have as few suppliers and contractors as possible

It might sound risky, but Patagonia prefers to be dependent on just a few suppliers that are, in return, dependent on them. Patagonia considers this a "true partnership." Founder Yvon Chouinard describes this strategy like this: "Our potential success is linked. We become like friends, family, mutually selfish business partners; what's good for them is good for us."

Don't measure your messaging against sales revenue

Patagonia wants to keep their messaging efforts simple: Share who they are, their values, their outdoor pursuits, and their passions. When it comes to measuring the value of that messaging, they don't even consider trying to conduct a square inch sales analysis of their catalog. They consider this analysis to be irrelevant and could create a culture focused on profits over purpose.

Never sacrifice quality

Whether its something as small as recalling malfunctioning pens or as impactful as closing hotels that cannot maintain Gold Standards, The Ritz-Carlton refuses to sacrifice on the quality of their product. Even during economically depressed times, they focused on providing maximum quality through efficiency rather than cutting corners. As co-founder Ed Staros remembers during the 1980s: "Just because the economy was bad, it did not mean the guest didn't want mouthwash."

This dedication has led The Ritz-Carlton to win the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award twice and pretty much every major award in the hospitality category.

Build your strategy by following the 3 Cs

- Collect data on everything: Over 40,000 Ritz-Carlton employees are responsible for collecting qualitative and quantitative data points on everything from the number of scuffs on elevator doors to how long it takes guests to become impatient at check-in. Data, that is not provided directly from staff, comes from guest comment cards, phone interviews, online questionnaires, and secret shoppers.

- Compile and analyze the information: All of the data is then reviewed through the lens of the company's five key success factors: Brand strength (the Mystique), employee engagement, customer engagement, product service excellence, and financial performance. Trends are then discovered and a SWOT analysis is performed in order to compare where they are today to their desired future state. The result is three to four priority measurements for each key success factor.

- Communicate your findings to everyone: The success factors and their measurements are then designed into a pyramid infographic with brand at the top and financial strength at the bottom. The pyramid is then prominently displayed in all staff areas. Department-level meetings are continuously held to discuss how each employee can personally impact the Key Success Factors and in turn impact the overall success of The Ritz-Carlton.

Measure engagement, not satisfaction

High satisfaction scores only tell you if customers are happy, not if they are loyal to your brand. So, The Ritz-Carlton began measuring customer engagement with Gallup's CE11 survey and employee engagement with Gallup's Q12 survey. By measuring both employee and customer engagement holistically, which Gallup refers to as HumanSigma, The Ritz-Carlton started to see the direct effect that employee engagement had on the customer experience.

Obsessively collect guest data to create personalized experiences

The Ritz-Carton staff are provided Guest Preference Pads, so they can write down notes about guests and later upload them to their customer relationship management (CRM) database. Any problem encountered or preference expressed, gets written down. Staff even do a quick Google search of guests to add their pictures to the database.

All of this information is then shared with staff during the morning lineup to help prepare for the day. The staff also are fed information through ear piece radios to help welcome guests by name and to make their stay more personal.

Create a continuous improvement system to battle MR BIV

Problems, mistakes, and defects will always occur but The Ritz-Carlton trains and encourages every employee to spot, report, and help solve these MR BIV sightings right away.

MR BIV (an acronym for Mistakes, Rework, Breakdowns, Inefficiencies, and Variations) is The Ritz-Carlton's way of continually trying to improve their systems.

Once a MR BIV has been identified, it's important to determine if the problem is a symptom of something larger. Staff begin by asking themselves 'Why' as many as five times to find the root cause, and then a permanent solution. For example, one Ritz-Carlton property was having problems with room service being late, so employees took it upon themselves to start asking 'Why.'

- Why? Answer: Waiters are waiting a long time for an elevator.

- Why? Answer: Elevators were being held up by the houseman.

- Why? Answer: The houseman was collecting linens from one floor to take to another.

- Why? Answer: There was a shortage of linens.

- Why? Answer: Linen inventory was cut to 80% occupancy.

- Solution: Order more linens.

But be careful to always receive MR BIV with open arms and a curious mind. Attacking or blaming employees for problems will only lead to them never helping you find a MR BIV again.

Make it easy to share best practices globally

The Ritz-Carlton has an innovation database where new proven problem resolutions can be shared with all of their hotels who may be facing similar challenges. The database has thousands of innovative solutions ranging from more effective ways to manage check-ins during busy times to introducing transportation vehicles for speedy beverage delivery on the beach.

Grade performance with a quality control checklist

At The Ritz-Carlton, for every four housekeepers, there is one person who spot checks their work against a quality control checklist. Scores are determined on a 100 point scale and anything below a 95% is considered below standard and requires a follow-up with the housekeeper to review what went wrong.

Don't follow the industry

Southwest co-founder Herb Kelleher used to say: “Conventional wisdom put a hell of a lot of airlines out of business.” In order to stay true to being the low-cost, reliable, fun airline, Southwest remained disciplined in avoiding popular trends and strategies used by competitors. Unlike other airlines, Southwest:

- Serves no meals, just snacks. Instead they added more seats in the empty spaces where meals would have been stored.

- Does not charge for the first two checked bags. They did the math and found it would take the fees of five or six bags to make up the revenue from one lost customer.

- Does not assign seats to travelers. This cuts down on boarding time by one to four minutes.

- Does not interline with other carriers. They avoid spending extra time and money on the ground waiting for passengers from delayed connecting flights.

- Avoids congested airports where flights can be unnecessarily lengthened or delayed by traffic.

- Does not use a hub-and-spoke model where planes and crews are always on standby. Instead, they use a point-to-point model that keeps planes flying as much as possible for more frequent flights.

- Broke away from stuffy uniforms and was the first airline to dress flight attendants in hot pants, which was later replaced by polo shirts and shorts.

Increase productivity and reduce costs by using only one type of equipment

By sticking with one type of plane, the Boeing 737, Southwest has been able to:

- Simplify training requirements enabling crew members to become experts of the plane inside and out

- Quickly and efficiently substitute aircrafts, reschedule flight crews, and transfer mechanics

- Reduce their inventory of parts which simplifies their record-keeping

- Negotiate better deals when purchasing new planes

Don't over plan

Southwest's philosophy has been to "not endlessly plan, discuss, and study in an effort to avoid the risk involved in actually making a decision." Instead, they gather the available facts as quickly as possible, make the necessary analysis, discuss it with the appropriate people, execute, and clean up any mistakes later.

- When Southwest was about to begin offering longer flights outside of Texas, there was concern that customers would want inflight meals. CEO Herb Kelleher's response was "Let's start flying and see."

- When Executive Vice President Gary Barron wanted to completely reorganize the management structure of Southwest's $700 million maintenance department, he presented CEO Herb Kelleher a 3-page proposal. After raising one concern that Gary addressed, Kelleher replied: "Then it's fine by me." The whole conversation took 4 minutes.

- After announcing service to San Diego, Southwest's construction permits got caught up in red tape. Instead of waiting, Southwest crew went ahead and put up a drywall screen, and started construction behind it. Their thought was they would either be granted a permit or have to tear it all down.

Growth is not a strategy, it's a tactic

In 2002, Starbucks' primary goal became to show Wall Street continued growth and increased comparative sales at all costs. As their store count tripled over the next five years, the Starbucks Experience weakened.

The warm environment became a sterile cookie-cutter template that could be easily replicated for new stores; the showmanship of coffee was replaced with button pushing; DVDs, CDs, and stuffed animals were front and center to increase daily store sales; and managers and staff were now trained by just being handed a "thick, three-ring binder of rules, techniques, and coffee information and was simply told to 'read it.'"

Slowly the amount of money each customer was spending in stores began to dip. By 2007, traffic slowed to the lowest levels in history and Starbucks was forced to close 8% of their US stores and let go over 12,000 people globally to stay in business.

Howard Schultz returned as CEO in 2008 and brought with him his own Transformation Agenda that he shared openly with the entire company in a ten part series. He wanted to refocus the company on one customer, one partner, and one cup of coffee at a time. To help free everyone to enthusiastically refocus on what was best for the customer, and not Wall Street, Starbucks would:

- Slow down the expansion of US locations, while closing underperforming stores that were opened haphazardly in the first place.

- No longer report same-store sales.

- Introduce the Pike Place Roast coffee blend to honor their history.

- Revamp their rewards program to build a stronger emotional connection with customers.

- Remove the sale of movie posters, CDs, DVDs, and stuffed animals in order to refocus on coffee.

- Close all stores for half a day in order to retrain baristas on the art of making an espresso.

- Redesign each store to be unique while being warm and inviting.

It took time but by June 2009, customer satisfaction began to rise again and Starbucks stock was on an upward trend rising 41%.

Let loyalists lead the way for expansion

Starting in the 1970s, Starbucks had begun building a customer-base through mail order. These coffee enthusiasts had discovered Starbucks either from vacationing in Seattle or having recently moved from the Seattle area. In their hometowns they began spreading awareness of Starbucks through their network of friends, who then began ordering from Starbucks as well. As Starbucks began to focus on nationwide expansion, Howard leveraged the data he had on this customer-base to decide where to open stores.

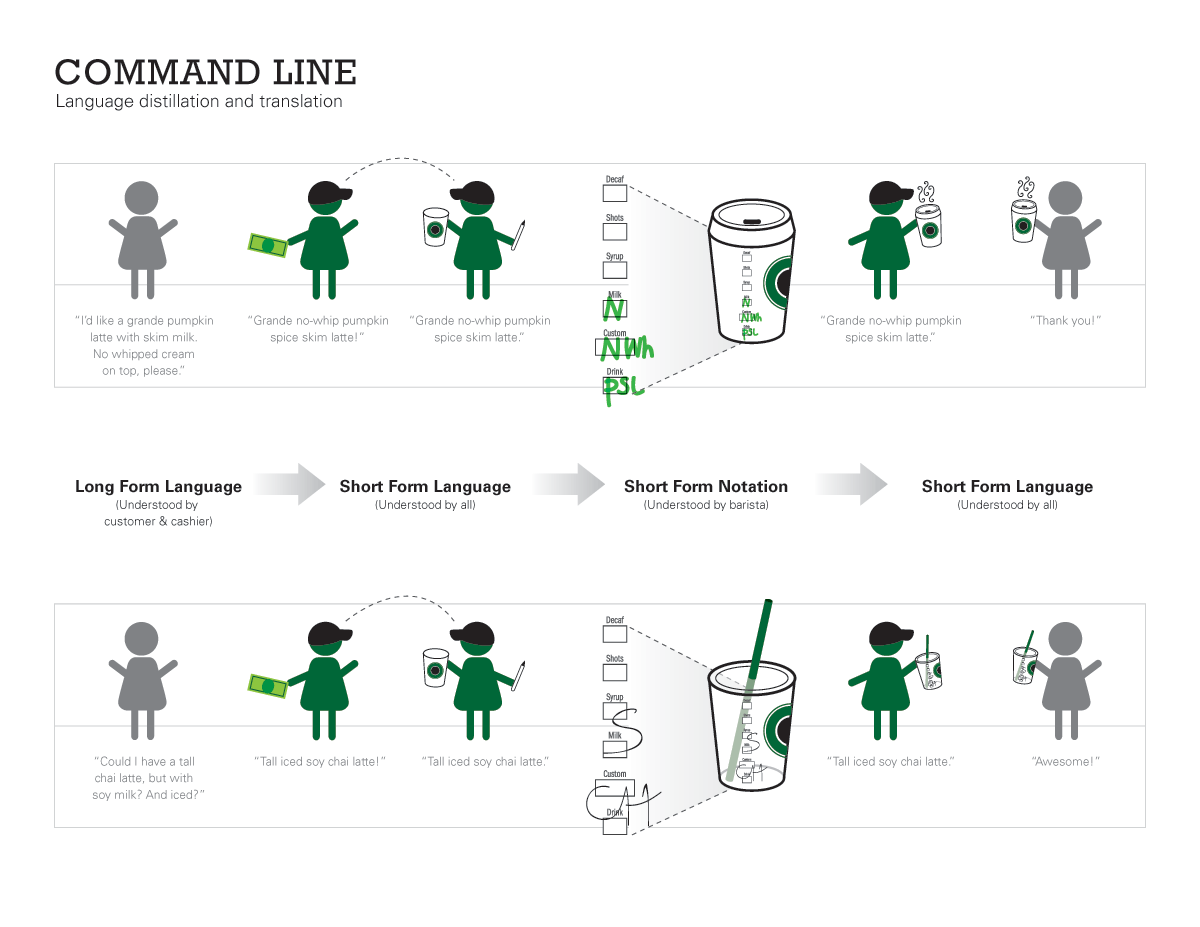

Keep it LEAN to improve customer satisfaction

Starbucks started using LEAN management techniques after seeing how one store manager took it upon herself to implement them and saw great results.

LEAN techniques removed any process that wasted time or took away from the customer experience. This allowed baristas to spend more time talking with customers and less time searching for things that were either in the wrong place or completely missing.

But former CEO, Howard Schultz feared that these practices would make Starbucks feel more like a factory run by a corporation rather than a local coffee shop. To avoid this, he ensured that headquarters would only provide the tools and training for LEAN techniques, and left it to the store managers to implement these techniques in their own unique way.

Some of the ways that Starbucks reduced redundancies and waste was to:

- Create color-coded preparation instructions for quick retention and understanding

- Move whips, drizzles, and chocolates closer to where they were needed to reduce steps behind the counter

- Use acronyms on coffee cups to help partners get every detail of the drink right and make those highly customized orders repeatable when they were ready

- Throw out the corporate manuals on supply room arrangements and customize everything for each specific store

- Take orders before customers get to the cash register

These changes might seem obvious but it wasn't until they started looking at every movement through LEAN that inefficiencies became clear. Within 6 months of implementation Starbucks customer satisfaction and quality scores had improved, productivity and revenue increased, and turnover dropped significantly.

Ensure that your vendors align with your values

Starbucks fully owns the coffee procurement process and all of their roasting facilities, but what about everything else? All other aspects of the supply chain are strictly monitored through what is called the Starbucks Coffee and Farmer Equity (CAFE) Practices. This helps to ensure that all vendors align with Starbucks values and quality standards.

CAFE Practices, developed by Starbucks staff, judge vendors on a set of over 200 indicators. Anyone scoring a 60 or above receives enhanced pricing and contract terms, while anything less requires you to go through the time and expense of re-verification in a year.

But even before CAFE Practices launched in 2004, vendors have always been judged on four criteria:

- Economic transparency: To reduce costs and improve efficiency through extensive service, cost, and productivity metrics.

- Social responsibility: To ensure a safe, fair, and humane work environment.

- Environmental leadership: To protect water quality, improve soil health, preserve biodiversity, reduce agrochemical use, and conserve water and energy.

- Quality: To ensure consistency by measuring everything from the altitude, variety, and even shade density of the coffee farms.

Think locally, not globally

In 1999, Starbucks opened their first store in China and a year later they expanded into Australia as well. By 2022, there were 4,200 stores in China and in Australia, 70% of its original 90 stores were closed. The difference? In Australia, Starbucks expanded rapidly and did not take the time to adapt to local preferences. In China, however, Starbucks took a more localized approach by:

- Adapting their menu to contain beverages based on local tea ingredients and foods that were more attuned to local tastes

- Incorporating traditional Chinese elements into the look and feel of their stores

- Working with local partners to source ingredients

- Adapting their recruitment techniques by inviting parents of potential staff to orientation days to get to know the brand better

Cut costs, not value or employee benefits

People wonder how Trader Joe's can keep prices low while also treating their employees well and turn a profit. To do this, Trader Joe's takes every opportunity to find ways to cut operational costs, like:

- Cutting hours of operation. Staying open long hours is a waste of energy and as a value retailer you don't need to differentiate yourself with hours.

- Not selling products that raise insurance costs. Kegs of beer and 5lb bags of sugar that come packed twelve to a bale were all discontinued because of risk of injury to the crew.

- Using free imagery. The iconic Trader Joe's 19th century imagery is used because these images are not subject to copyright laws.

- Using cheap shelving. Not only is warehouse shelving cheap, it is also inexpensive to change, and can be easily assembled and disassembled by any employee.

- Buying in bulk and paying in cash. "This means giant 40-50 lbs wheels of cheese at a time. The products are being sent to the TJ kitchen or warehouse where it's being processed.

- Avoiding brand name products. 80% of Trader Joe's products fall under their own label where they cut out the middleman by buying food directly from the source and doing all the packaging themselves.

- Taking advantage of discontinuities. If a vendor had leftover eggs or some unusual product that they couldn't get rid of, Trader Joe's buys it at a low price, repackages it, and sells it.

- Keeping their stores small because big stores just cost too much

Align your budgeting model to your values

Instead of corporate budgeting, Trader Joe's leaves setting targets, planning, and forecasting up to each individual store. This decentralized approach reinforces two of the brand's values:

- KAIZN: This means everybody in the company owes everybody else a better job every day, every year in what they do. So all that corporate expects is that each store do a little better than the previous year.

- We're a national chain of neighborhood grocery stores: Stores are treated as their own entity allowing managers to focus on doing what's right for its neighborhood and customers, rather than focusing on corporate goals.

Only open super-volume stores

When looking to open a new Trader Joe's, founder Joe Coulombe's strategy was to "have a few stores, as far apart as possible, and to make them as high volume as possible." To do this, Joe would:

- Keep to the same demographics. Trader Joe's would seek out areas that attracted the underpaid and overeducated. This included locations near major institutions of learning, hospitals, and high tech corporate offices. It also included "semi-decayed neighborhoods, where...the mortgages were all paid-down,...the kids had left home..." and housing and rental prices were cheaper and more suitable for those "underpaid academics." Each area had to have a high number of households, no less than 40,000, with at least 66% being in their target audience.

- Look for locations with excellent boulevard access. Trader Joe's would avoid easy freeway access as those locations are more prone to holdups.

- Avoid cannibalization of other stores. Instead of measuring the distance between stores using miles, Trader Joe's kept a rule that stores should be no less than twenty minutes apart.

- Avoid areas where people are "strapped" with high mortgages. Sure these families may have high incomes but Trader Joe's considers them "the poorest of the poor" because they are burdened with mortgages and saving for their children's colleges. In Joe's opinion, these people are better off shopping at Costco.

- Avoid areas that do not represent the core customer's values. When driving around the area of a potential store, if Joe Coulombe saw too many campers and speedboats he would cross the option from the list. As he puts it: "People who consume high levels of fossil fuel don't fit the Trader Joe's profile."

As a result, Trader Joe's achieves sales of $1,000/sq foot of total area, while supermarkets $570/sq foot of sales area.

Don't put faith in market testing

As Joe Coulombe wrote: "Each year, 22,000 new products are introduced to the grocery trade, most of them from big guns like Procter & Gable or Colgate, who have conducted elaborate test marketing before going nationwide. Ninety percent of these new products fail."

Instead, Trader Joe's takes a different approach placing small orders of new products and if they sell they order more—if not, leftovers go to charity.

Don't secretly collect data on your customers

As Trader Joe's sees it, collecting customers' data is like spying on them. That is why, even in the age of analytics and AI, they don't have membership accounts, customer relationship management systems, or any other systems to segment, track, or categorize their customers' habits. Instead, they rely on gaining direct feedback from their customers during their daily interactions.

Give generously but be strategic about it

When it comes to non-profit giving, the Trader Joe's philosophy is to give generously but to always:

- Reach your core audience: As a grocer for the overeducated and underpaid, Trader Joe's limits their non-profit giving to events that only those people would attend. This includes pledge drives, museum and art gallery openings, hospital benefits, college alumni gatherings, and chamber orchestra benefits.

- Promote your brand effectively: Never give cash and never buy space in a program. To Trader Joe's, these are a "waste of money" with little to no return. Instead, they focus on donating branded products that add to the experience of an event.

- Be cost efficient: While champagne is always highly requested at events, Trader Joe's never donates it because the "federal excise tax on sparkling wine is way too much." Instead, they stick to donating more cost efficient products, like wine.

Test every product in the harshest conditions

There is no 'pay to play' to get your product on a Trader Joe's shelf, like in most supermarkets. Instead, every product goes through a rigorous Tasting Panel where only 10% of the products actually pass the test.

These Testing Panels are designed to remove any romance and story from the product. "There's nothing in there that makes it comfortable...It's like a cold war interrogation booth, because we want the products that succeed to go through this like ultra-Darwinian exercise to say that they could stand up even to that harshest light of critical evaluation."

If a product passes with a 70% or more approval rating, it is only then that Trader Joe's asks about the price. Then the bargaining begins and "if the cost is too high and we can't get it for less, we won't buy it."

Outsource anything that isn't central to your primary role

Since 1977, Trader Joe's has run its operations on the philosophy that you should outsource anything that isn't central to your primary job. And for Trader Joe's that's everything except buying and selling. As founder Joe Coulombe wrote: "We got rid of our own maintenance people, we sold off almost all the real estate we had acquired during the 1970s, we never took mainframe computing in-house."

Measure the quality of your service

To prove to themselves that they are continually improving in service, Umpqua Bank began measuring customer and staff service quality. The scores are calculated each month, teams are ranked, and the results are posted for everyone.

The goal is to reward team performance, not individual accomplishment. The winning store and department both receive a crystal trophy that they proudly display until it moves on to the next winner the following month. Any store or department that ranks poorly for some time is asked to develop an improvement plan and then is held accountable for implementing it.

Store Return on Quality (ROQ) Measurements

- Sales Effective Ratio (SER) measures the average number of bank products and services sold to new customers at each sales session.

- Customer Account Retention measures the number of deposits closed as a percentage of all accounts.

- Customer Service Surveys measure the quality of service that customers receive.

- New Account Surveys measure the average score of new account holders.

- Telephone Shopping Reports are done three times per month by outside vendors. They measure whether the phones are answered correctly and if the associate asks if the customer needs additional information.

- New Deposit & Loan Accounts / Full-time Equivalent measures the total number of deposits and loans divided by the number of employees working in the store.

Department Return on Quality Measurements

Departments at Umpqua each have developed service-level agreements (SLA) with one another. These agreements include standards such as turnaround time. Every associate who interacts with a specific department provides both positive and negative feedback to that department with an SLA survey.

Don't hunker down in times of uncertainty

During the Great Recession, Umpqua Bank had no layoffs and didn't reduce costs. While this was the strategy of many companies, former CEO Ray Davis instead invested in Umpqua's capacity. He explains, "How can we weather the storm by reducing our resources? When you are in stormy seas, you call out, 'All hands on deck,' you don't tell half of them to jump overboard...The last thing we wanted to do was weaken our ability to create our own future."

Even though their earnings took a hit, Umpqua emerged from the Great Recession quickly and with a stronger balance sheet than ever before. Ray attributes this to Umpqua's ability not to hunker down but instead invest in opportunities like:

- Creating an international banking division

- Adding a wealth management division

- Expanding commercial banking operations in Seattle

- Adding a capital markets division

But this doesn't mean Umpqua condones retaining excess overhead. Ray clarifies, "I am as much for efficiency as anyone, but why wait for problems to run your company as efficiently as possible?"

Measure service with Net Promoter Score (NPS)

After any order or after certain customer interactions, Zappos sends out email surveys to these customers in order to help calculate their Net Promoter Score and learn more about the experiences the customers received. Questions have included:

- On a scale of 0 to 10, 10 being the highest score, how likely are you to recommend Zappos to a friend or a family member?

- If you had to name one thing that we could improve upon, what would that be?

- During your last interaction with us, you contacted a member of our Customer Loyalty Team. On a scale of 0 to 10, if you had your own company that was focused upon service, how likely would you be to hire this person to work for you?

- Overall, would you describe the service you received from [team member name] as good, bad, or fantastic?

- What exactly stood out as being good or bad about this service?

Results are then calculated each day and shared with the entire company. Each team member also receives their own individual scores for the calls they specifically handled.